Generating Artificial Yeast DNA Sequences using a DNA LLM

Under Development!

This tutorial is not in its final state. The content may change a lot in the next months. Because of this status, it is also not listed in the topic pages.

| Author(s) |

|

OverviewQuestions:

Objectives:

How do you set up a computational environment for generating synthetic DNA sequences using pre-trained language models?

What role does the temperature parameter play in controlling the variability of generated DNA sequences?

How can you compare generated synthetic DNA sequences with real genomic sequences using k-mer counts and PCA?

What is the significance of performing BLAST searches on generated DNA sequences, and how do you interpret the results?

How can you detect open reading frames (ORFs) in generated DNA sequences and translate them into amino acid sequences?

Requirements:

Describe the process of generating synthetic DNA sequences using pre-trained language models and explain the significance of temperature settings in controlling sequence variability.

Set up a computational environment (e.g., Google Colab) and configure a pre-trained language model to generate synthetic DNA sequences, ensuring all necessary libraries are installed and configured.

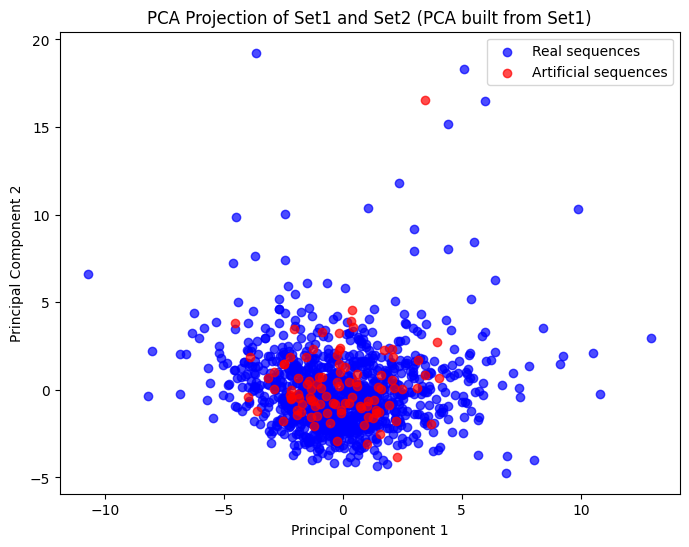

Use k-mer counts and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to compare generated synthetic DNA sequences with real genomic sequences, identifying similarities and differences.

Perform BLAST searches to assess the novelty of generated DNA sequences and interpret the results to determine the biological relevance and uniqueness of the synthetic sequences.

Develop a pipeline to detect open reading frames (ORFs) within generated DNA sequences and translate them into amino acid sequences, demonstrating the potential for creating novel synthetic genes.

- tutorial Hands-on: Introduction to Python

- tutorial Hands-on: Python - Warm-up for statistics and machine learning

- slides Slides: Foundational Aspects of Machine Learning using Python

- tutorial Hands-on: Foundational Aspects of Machine Learning using Python

- slides Slides: Neural networks using Python

- tutorial Hands-on: Neural networks using Python

- slides Slides: Deep Learning (without Generative Artificial Intelligence) using Python

- tutorial Hands-on: Deep Learning (without Generative Artificial Intelligence) using Python

- tutorial Hands-on: Pretraining a Large Language Model (LLM) from Scratch on DNA Sequences

- tutorial Hands-on: Fine-tuning a LLM for DNA Sequence Classification

- tutorial Hands-on: Predicting Mutation Impact with Zero-shot Learning using a pretrained DNA LLM

Time estimation: 3 hoursLevel: Intermediate IntermediateSupporting Materials:Published: Apr 17, 2025Last modification: Apr 17, 2025License: Tutorial Content is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. The GTN Framework is licensed under MITpurl PURL: https://gxy.io/GTN:T00521version Revision: 1

Best viewed in a Jupyter NotebookThis tutorial is best viewed in a Jupyter notebook! You can load this notebook one of the following ways

Run on the GTN with JupyterLite (in-browser computations)

Launching the notebook in Jupyter in Galaxy

- Instructions to Launch JupyterLab

- Open a Terminal in JupyterLab with File -> New -> Terminal

- Run

wget https://training.galaxyproject.org/training-material/topics/statistics/tutorials/genomic-llm-sequence-generation/statistics-genomic-llm-sequence-generation.ipynb- Select the notebook that appears in the list of files on the left.

Downloading the notebook

- Right click one of these links: Jupyter Notebook (With Solutions), Jupyter Notebook (Without Solutions)

- Save Link As..

Generating synthetic DNA sequences using pre-trained language models bridges the fields of synthetic biology and artificial intelligence, enabling the creation of novel DNA sequences that closely mimic natural genomes. By leveraging the power of advanced language models, we can generate biologically relevant sequences that have the potential to revolutionize genetic engineering, drug discovery, and our understanding of genomic function.

Throughout this tutorial, we will learn how to set up a computational environment tailored for DNA sequence generation, configure pre-trained language models to produce synthetic sequences, and analyze the results to assess their biological significance. Here the aim is to generate DNA sequences similar to yeast, more specifically to Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

For this tutorial, we’ll use a pre-trained language model which was trained on 1,011 Saccharomyces cerevisiae isolates from Peter et al. 2018. This model has 138 million parameters and uses a mixture of experts architecture, making it efficient and powerful for generating DNA sequences.

model_name = "RaphaelMourad/Mistral-DNA-v1-138M-yeast"

AgendaIn this tutorial, we will cover:

Prepare resources

Install dependencies

The first step is to install the required dependencies:

!pip install Bio==1.7.1

!pip install orfipy

!pip install sklearn

!pip install transformers -U

!pip install torch==2.5.0

Import Python libraries

Let’s now import them.

import os

import itertools

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import orfipy_core

import pandas as pd

import torch

from Bio import (SeqIO, Seq)

from collections import defaultdict

from sklearn.decomposition import PCA

from transformers import pipeline

from typing import List, Tuple

Comment: VersionsThis tutorial has been tested with following versions:

numpy> 1.26.4transformers> 4.47.1You can check the versions with:

np.__version__ transformers.__version__

Check and configure available resources

Let’s check the GPU usage and RAM:

!nvidia-smi

Let’s configure PyTorch and the CUDA environment – software and hardware ecosystem provided by NVIDIA to enable parallel computing on GPU – to optimize GPU memory usage and performance:

-

Enables CuDNN benchmarking in PyTorch:

torch.backends.cudnn.benchmark=True -

Set an environment variable that configures how PyTorch manages CUDA memory allocations

os.environ["PYTORCH_CUDA_ALLOC_CONF"] = "max_split_size_mb:32"

Generate Synthetic DNA Sequences

Using the pre-trained language model which was trained on 1,011 Saccharomyces cerevisiae isolates, we would like to generate 100 synthetic yeast DNA sequences.

Build the Sequence Generator

First, we need to set up the sequence generation pipeline. This pipeline will enable us to generate synthetic DNA sequences that mimic natural genomic sequences. By leveraging the power of language models, we can create novel DNA sequences for various applications in synthetic biology.

We use the pipeline function from the transformers library which simplifies the process of setting up a sequence generation pipeline. It abstracts away the complexities of model loading and configuration, allowing us to focus on generating sequences.

generator = pipeline("text-generation", model=model_name)

Question

- What do the parameters

"text-generation"?- What is a pipeline?

- What are the different types of pipelines?

It specifies that we are creating a pipeline for text generation, which is suitable for generating DNA sequences.

Pipelines are high-level abstractions that simplify the process of applying models to various NLP tasks

Besides text-generation, there are several other types of pipelines designed for different applications. Here are some of the most commonly used pipelines:

feature-extraction: Extracts features (embeddings) from text using a model. Useful for tasks that require text representation, such as clustering or similarity measurement.sentiment-analysis: Determines the sentiment of a given text, classifying it as positive, negative, or neutral.text-classification: Classifies text into predefined categories or labels, useful for tasks like spam detection, topic classification, etc.token-classification: Assigns a label to each token in the input text, commonly used for Named Entity Recognition (NER) and Part-Of-Speech (POS) tagging.question-answering: Answers questions based on a given context or passage of text. Useful for building Q&A systems.fill-mask: Predicts the missing word(s) in a sentence with a masked token, often used with models like BERT.summarization: Generates a concise summary of a longer text, useful for creating abstracts or condensing information.translation: Translates text from one language to another, supporting various language pairs.conversational: Engages in a conversation by generating responses based on input prompts, useful for building chatbots.zero-shot-classification: Classifies text into categories that were not seen during training, allowing for flexible and dynamic classification tasks.table-question-answering: Answers questions based on structured data, such as tables, combining NLP with data querying capabilities.Each of these pipelines is designed to handle specific NLP tasks efficiently, leveraging pre-trained models to provide accurate and fast results. You can initialize these pipelines using the pipeline function from the transformers library, specifying the task you want to perform.

Generate Synthetic DNA Sequences

Once the pipeline is set up, we can generate synthetic DNA sequences by calling the generator with appropriate parameters. We first need to specify the parameters for sequence generation:

-

Maximum length of the generated sequence in term of tokens (i.e. k-mers of 3 to 7 bases)

max_length = 30 -

Number of sequences to generate

num_sequences = 100 -

The temperature:

It controls the randomness of the generated sequences. A higher temperature results in more varied outputs, while a lower temperature produces more deterministic sequences.

temperature = 0.1

Let’s now generate the sequences:

synthetic_dna = generator(

"",

max_length=max_length,

do_sample=True,

top_k=50,

temperature=temperature,

repetition_penalty=1.2,

num_return_sequences=num_sequences,

eos_token_id=0,

)

QuestionWhat do the parameters?

""do_sample=Truetop_k=50repetition_penalty=1.2eos_token_id=-0

Starting prompt (empty for unconditional generation)

do_sample=True: When set toTrue, the model uses sampling to generate sequences, which introduces randomness and variability in the output.top_k=50: Limits the generated tokens to the top k most probable tokens. This helps in controlling the diversity of the output while ensuring biological relevance.repetition_penalty=1.2: Penalizes the repetition of the same token in the generated sequence. A value greater than 1.0 discourages the model from repeating tokens, promoting diversity.eos_token_id=0: Specifies the end-of-sequence token ID, which signals the model to stop generating further tokens. This is useful for controlling the termination of sequence generation

Let’s extract the sequences:

artificial_sequences=[]

for seq in synthetic_dna:

artificial_sequences.append(seq["generated_text"].replace(" ", ""))

QuestionWhat is the length of the 5 first sequences?

for i in range(4): print(len(artificial_sequences[i]))

To generate artificial DNA sequence starting by a defined substring, e.g. “TATA”, we replace

""ingeneratorfunction by the defined substring:synthetic_dna = generator( "TATA", max_length=max_length, do_sample=True, top_k=50, temperature=0.4, repetition_penalty=1.2, num_return_sequences=100, eos_token_id=0, ) artificial_sequences = [seq["generated_text"].replace(" ", "") for seq in synthetic_dna] artificial_sequences[0:5]

Compare with Real Yeast Genome

We would like to compare the generated sequences to real sequences from Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Let’s download the yeast genome assembly:

!wget http://hgdownload.soe.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/sacCer3/bigZips/sacCer3.fa.gz

!gunzip sacCer3.fa.gz

We would like now to extract 1,000 random sequences of a length 100 bases from the downloaded genome:

def extract_random_sequences(

genome_file: str,

seq_length: int = 100,

num_seqs: int = 100,

) -> List[str]:

"""

Extracts random sequences from a genome FASTA file.

Parameters:

- genome_file (str): Path to the genome FASTA file.

- seq_length (int): Length of each sequence to extract.

- num_seqs (int): Number of sequences to extract.

Returns:

- List[str]: A list of extracted sequences.

"""

try:

# Load genome sequences from the FASTA file

genome = [str(record.seq) for record in SeqIO.parse(genome_file, "fasta")]

# Join all chromosomes or scaffolds into one large sequence

genome_seq = "".join(genome)

genome_size = len(genome_seq)

if genome_size < seq_length:

raise ValueError("Sequence length is larger than the genome size.")

# List to store extracted sequences

extracted_seqs = []

# Extract random sequences

for _ in range(num_seqs):

start_pos = random.randint(0, genome_size - seq_length) # Random start position

sequence = genome_seq[start_pos:start_pos + seq_length] # Extract sequence

extracted_seqs.append(sequence)

return extracted_seqs

except Exception as e:

print(f"An error occurred: {e}")

return []

genome_file = "sacCer3.fa" # Path to the yeast genome FASTA file

real_sequences = extract_random_sequences(genome_file, seq_length=100, num_seqs=1000)

To compare synthetic and real DNA sequences, we utilize k-mer counts as a method to numerically describe and analyze DNA sequences. K-mers are short, overlapping subsequences of a fixed length \(k\) within a DNA sequence. We can think of k-mers as “words” within the DNA sequence. Just as paragraphs in text share common words, similar DNA sequences will share common k-mers. By counting the occurrences of these k-mers, we can transform DNA sequences into numerical vectors, allowing us to compare them quantitatively. Sequences that are very similar are expected to have similar k-mer counts, much like how similar texts share common vocabulary. By comparing the k-mer counts of synthetic and real DNA sequences, we can assess their similarity. If two sequences share many k-mers, it indicates that they are likely to be similar in composition and structure.

This approach leverages the power of k-mer analysis to provide insights into the similarity between synthetic and real DNA sequences, aiding in the validation and evaluation of synthetic biology techniques.

def generate_all_kmers(k: int) -> List[str]:

"""

Generate all possible k-mers of a given length.

Parameters:

- k (int): Length of each k-mer.

Returns:

- List[str]: A list of all possible k-mers.

"""

return ["".join(p) for p in itertools.product("ACGT", repeat=k)]

def kmer_counts_matrix(sequences: List[str], k: int = 6) -> Tuple[np.ndarray, List[str]]:

"""

Compute k-mer counts for a list of sequences and return a count matrix.

Parameters:

- sequences (List[str]): List of DNA sequences.

- k (int): Length of each k-mer. Default is 6.

Returns:

- Tuple[np.ndarray, List[str]]: A tuple containing the k-mer count matrix and the list of all possible k-mers.

"""

all_kmers = generate_all_kmers(k)

kmer_index = {kmer: idx for idx, kmer in enumerate(all_kmers)} # Map k-mers to column indices

matrix = np.zeros((len(sequences), len(all_kmers)), dtype=int) # Initialize count matrix

for seq_idx, seq in enumerate(sequences):

if len(seq) < k:

raise ValueError(f"Sequence length is less than {k} for sequence {seq_idx}: {seq}")

kmer_dict = defaultdict(int)

for i in range(len(seq) - k + 1):

kmer = seq[i:i+k]

kmer_dict[kmer] += 1

# Fill in the matrix for this sequence

for kmer, count in kmer_dict.items():

if kmer in kmer_index:

matrix[seq_idx, kmer_index[kmer]] = count

return matrix, all_kmers

Let’s now count 4-mers for artificial and real sequences.

k = 4

artificial_seq_kmer_counts, kmers = kmer_counts_matrix(artificial_sequences, k=k)

real_seq_kmer_counts, kmers = kmer_counts_matrix(real_sequences, k=k)

Question

- What is the format of

artificial_seq_kmer_countsandreal_seq_kmer_counts?- What are the dimensions?

artificial_seq_kmer_countsandreal_seq_kmer_countsare 2-matrices.- 100 x 256 (\(256 = 4^{4}\))

To visualize and compare real and generated DNA sequences in a continuous space, we can utilize Principal Component Analysis (PCA). PCA is a powerful dimensionality reduction technique that transforms high-dimensional data into a lower-dimensional space while preserving as much variability as possible. This allows us to visualize the similarities and differences between the sequences effectively.

def plot_pca_projection(set1: np.ndarray, set2: np.ndarray, title: str = "PCA Projection") -> None:

"""

Fit PCA on set1 and project both set1 and set2 into the PCA space, then plot the results.

Parameters:

- set1 (np.ndarray): K-mer count matrix for the first set of sequences (used to fit PCA).

- set2 (np.ndarray): K-mer count matrix for the second set of sequences (projected into PCA space).

- title (str): Title of the plot.

Returns:

- None

"""

# Fit PCA on set1 only

pca = PCA(n_components=2)

pca.fit(set1)

# Project both set1 and set2 into the PCA space

pca_set1 = pca.transform(set1)

pca_set2 = pca.transform(set2)

# Plot the first two principal components

plt.figure(figsize=(8, 6))

plt.scatter(

pca_set1[:, 0],

pca_set1[:, 1],

color="blue",

label="Real sequences",

alpha=0.7,

)

plt.scatter(

pca_set2[:, 0],

pca_set2[:, 1],

color="red",

label="Artificial sequences",

alpha=0.7,

)

# Add labels and legend

plt.xlabel("Principal Component 1")

plt.ylabel("Principal Component 2")

plt.title(title)

plt.legend()

# Show the plot

plt.show()

plot_pca_projection(real_seq_kmer_counts, artificial_seq_kmer_counts)

Hands OnFor different temperature values (\(0.001\), \(0.01\), \(0.1\), \(0.5\), \(1.0\), \(1.5\)):

- Generate synthetic DNA sequences

- Observe the 5 first generated sequences

- Generate the PCA plots

- Compute the variance of k-mers counts between artificial sequences

def generate_synthetic_dna( model_name: str, max_length: int, num_sequences: int, temp: float, top_k: int = 50, repetition_penalty: float = 1.2, ) -> List[str]: """ Generate synthetic DNA sequences using a pre-trained language model. Parameters: - model_name (str): Name or path of the pre-trained model. - max_length (int): Maximum length of each generated sequence. - num_sequences (int): Number of sequences to generate. - temp (float): Temperature value to control sequence variability. - top_k (int): Number of highest probability vocabulary tokens to consider. Default is 50. - repetition_penalty (float): Penalty for repeating the same token. Default is 1.2. Returns: - List[str]: List of generated DNA sequences. """ # Initialize the sequence generation pipeline generator = pipeline("text-generation", model=model_name) # Generate synthetic DNA sequences synthetic_dna = generator( "", max_length=max_length, do_sample=True, top_k=top_k, temperature=temp, repetition_penalty=repetition_penalty, num_return_sequences=num_sequences, eos_token_id=0, ) # Extract and clean the generated sequences artificial_sequences = [seq["generated_text"].replace(" ", "") for seq in synthetic_dna] return artificial_sequences temperatures = [0.001, 0.01, 0.1, 0.5, 1.0, 1.5] for temp in temperatures: art_sequences = generate_synthetic_dna(model_name, max_length, num_sequences, temp) art_seq_kmer_counts, kmers = kmer_counts_matrix(art_sequences, k=k) plot_pca_projection(real_seq_kmer_counts, art_seq_kmer_counts) var = np.mean(np.var(art_seq_kmer_counts, axis=0)) print(f"Variance for temperature of { temp }: { var }")

Question

- How similar do the 5 first generated DNA sequences look like given the temperature?

- What are the different values for the variance?

- What can we conclude?

- Lower the temperature, more similar the sequences.

- The variance for the different temperatures are:

- Variance \(=\) for temperature \(= 0.001\)

- Variance \(=\) for temperature \(= 0.01\)

- Variance \(=\) for temperature \(= 0.1\)

- Variance \(=\) for temperature \(= 0.5\)

- Variance \(=\) for temperature \(= 1\)

- Variance \(=\) for temperature \(= 1.5\)

- Higher the temperature, higher the variance, higher the variability.

Checking for Novelty in Generated DNA Sequences Using BLAST

After generating synthetic DNA sequences, it’s crucial to verify whether these sequences are truly novel or if they closely resemble existing sequences in biological databases. One effective method to accomplish this is by performing a BLAST (Basic Local Alignment Search Tool) search (Altschul et al. 1990). BLAST allows us to compare our generated sequences against a comprehensive database of known DNA sequences, helping us determine their uniqueness and potential biological relevance.

Let’s start with a synthetic DNA sequence generated with a low temperature setting. Low temperature settings reduce variability, making the generated sequences more similar to real sequences. This step helps ensure that the sequence is biologically plausible and likely to have counterparts in existing databases.

Hands On

- Generate the synthetic DNA sequences with a temperature value of \(0.01\)

- Get the first sequence

- Make a Standard Nucleotide BLAST search of the first sequence

art_sequences = generate_synthetic_dna(model_name, max_length, num_sequences, 0.01) art_sequences[0]

Question

- How many significant similarities have been found?

- Have we generated new sequence?

- The BLAST search do not return any significant match

- When the BLAST search returns no significant matches, it suggests that the synthetic sequence is novel and does not closely resemble any known sequences. This outcome is particularly interesting because it indicates that the sequence generation process has produced something entirely new.

When generating sequences with low temperature, we observed limited variability among the sequences. This lack of variability can be useful for ensuring consistency but may limit the exploration of novel sequence spaces. To introduce more variability and potentially discover even more novel sequences, we can increase the temperature setting during sequence generation. Higher temperatures introduce greater randomness, leading to more diverse and potentially unique sequences.

Hands On

- Generate the synthetic DNA sequences with a temperature value of \(1\)

- Get the first sequence

- Make a Standard Nucleotide BLAST search of the first sequence

art_sequences = generate_synthetic_dna(model_name, max_length, num_sequences, 1) art_sequences[0]

Question

- How many significant similarities have been found?

- Have we generated new sequence?

- The BLAST search do not return any significant match

- When the BLAST search returns no significant matches, it suggests that the synthetic sequence is novel and does not closely resemble any known sequences. This outcome is particularly interesting because it indicates that the sequence generation process has produced something entirely new.

Even if the generated sequences are novel, novelty alone does not guarantee functionality, so further analysis may be necessary to assess the potential applications of these sequences.

Exploring Synthetic Gene Generation

Having successfully generated and analyzed synthetic DNA sequences, the next intriguing question is: Can we extend this approach to generate entire synthetic genes? This endeavor requires producing longer sequences that mimic the complexity and functionality of natural genes. The mean length of yeast genes is several hundred bases. To effectively mimic natural genes, our synthetic sequences must match this length while maintaining biological plausibility. Generating longer sequences is not merely about increasing length; it’s about ensuring that these sequences contain the necessary genetic elements, such as promoters, coding regions, and regulatory sequences, that are essential for gene function.

To start, we generate 10 sequences with max_length = 400:

synthetic_dna = generate_synthetic_dna(model_name, 400, 10, 1)

QuestionHow long are the first 5 sequences?

Detecting Open Reading Frames (ORFs)

To determine if the generated sequences could contain genes, we examine them for the presence of key genetic elements, such as Open Reading Frames (ORFs).

An ORF is a portion of a DNA sequence that begins with a start codon (e.g., ATG) and ends with a stop codon (e.g., TAA, TAG, TGA). Identifying ORFs is essential for determining the potential functionality of synthetic DNA sequences, as ORFs can indicate whether a sequence could encode a protein.

To detect ORFs in sequences, we use orfipy_core:

def detect_orfs(

sequence: str,

minlen: int = 100,

maxlen: int = 1000,

) -> List[Tuple[int, int, str, str]]:

"""

Detect ORFs in a given DNA sequence.

Parameters:

- sequence (str): The DNA sequence to analyze.

- minlen (int): Minimum length of ORFs to detect. Default is 100.

- maxlen (int): Maximum length of ORFs to detect. Default is 1000.

Returns:

- List[Tuple[int, int, str, str]]: List of ORFs with start, stop positions, strand, and description.

"""

orfs = []

for start, stop, strand, description in orfipy_core.orfs(sequence, minlen=minlen, maxlen=maxlen):

orfs.append((start, stop, strand, description))

print(f"Start: {start}, Stop: {stop}, Strand: {strand}, Description: {description}")

return orfs

Let’s extract the ORFs for the first DNA sequence:

seq = artificial_sequences[0]

orfs = detect_orfs(seq)

QuestionHow many ORFs have been detected for the first DNA sequence?

Extracting and Translating Detected Open Reading Frames (ORFs)

After detecting Open Reading Frames (ORFs) in our synthetic DNA sequences, the next step is to extract these ORFs and translate them into protein sequences. This process allows us to explore the potential protein products encoded by our synthetic genes, providing insights into their possible functions and biological roles.

To extract and translate the ORFs, we need to:

- Extract the ORF Sequence: Using the start and stop positions identified by the

detect_orfsfunction, we can extract the corresponding DNA sequence for each ORF. This sequence represents the potential protein-coding region within the synthetic DNA. - Translate the ORF: We can convert the DNA sequence of the ORF into its corresponding amino acid sequence. This step reveals the potential protein product encoded by the ORF.

def extract_and_translate_orf(

sequence: str,

orfs: List[Tuple[int, int, str, str]],

orf_index: int = 0,

) -> str:

"""

Extract an ORF from a DNA sequence and translate it into a protein sequence.

Parameters:

- sequence (str): The DNA sequence containing the ORF.

- orfs (List[Tuple[int, int, str, str]]): List of detected ORFs with start, stop positions, strand, and description.

- orf_index (int): Index of the ORF to extract and translate. Default is 0.

Returns:

- str: The translated protein sequence.

"""

# Extract the ORF sequence using the start and stop positions

start, stop, strand, description = orfs[orf_index]

orf_sequence = sequence[start:stop]

# Translate the ORF sequence into a protein sequence

protein_sequence = str(Seq(orf_sequence).translate())

return protein_sequence

For the first detected ORFs:

protein_seq = extract_and_translate_orf(seq, orfs)

print(f"Translated Protein Sequence: {protein_seq}")

After translating a synthetic DNA sequence into a protein sequence, the next crucial step is to analyze this sequence to uncover its potential biological function. This involves identifying known protein domains or motifs within the sequence that may indicate specific functions, such as binding sites or active regions. Verifying the biological plausibility of the translated sequence is essential, which can be achieved by comparing it to known protein sequences in databases like UniProt or GenBank using tools like Diamond and InterProScan. Additionally, examining the conservation of the sequence across different species can provide insights into its functional importance. If the sequence shows potential for biological function, it can serve as a starting point for further research, including structural modeling to predict its three-dimensional structure, functional assays to test its activity, and evolutionary studies to understand its origins and adaptations. This comprehensive analysis not only enhances our understanding of the generated sequences but also opens new avenues for scientific exploration and application in synthetic biology and genetic engineering.

Conclusion

Throughout this tutorial, we have explored the process of generating synthetic DNA sequences using a DNA Language Model (LLM), focusing on creating sequences that mimic the complexity and functionality of natural yeast genomes. We began by building a sequence generator, leveraging pre-trained models to produce synthetic DNA sequences with controlled variability.

We compared of these synthetic sequences to real yeast genomes, utilizing k-mer counts and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to visualize and assess their similarities and differences. This comparative analysis provided valuable insights into how well our generated sequences aligned with natural counterparts, highlighting both the strengths and areas for improvement in our approach.

To ensure the novelty of our generated sequences, we conducted BLAST searches, confirming that many of our synthetic sequences were indeed unique and did not closely match existing sequences in biological databases. This step was crucial in validating the potential of our model to produce truly innovative DNA sequences.

Expanding our exploration, we delved into the realm of synthetic gene generation. By detecting Open Reading Frames (ORFs) within our synthetic sequences, we identified potential protein-coding regions that could be translated into amino acid sequences. This process allowed us to analyze the biological relevance and potential functions of the proteins encoded by our synthetic genes, opening avenues for further research and application.

In conclusion, this tutorial has demonstrated the power and potential of DNA LLMs in generating synthetic DNA sequences and exploring synthetic gene generation. By combining advanced computational techniques with biological insights, we have shown how to create novel sequences that not only mimic natural genomes but also offer new possibilities for synthetic biology and genetic engineering. As we continue to refine these methods, the future holds exciting prospects for innovation and discovery in the field of genomics.